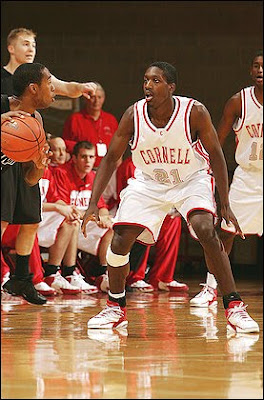

Cornell's Khaliq Gant before his injury as a sophomore during the 2005-06 season. He was hurt while diving for a loose ball in practice.

Cornell's Khaliq Gant before his injury as a sophomore during the 2005-06 season. He was hurt while diving for a loose ball in practice.By Kathy Orton

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Cornell was stunned by the loss to Columbia. The Big Red couldn't understand how it let this game slip away. The team had suffered yet another ruinous collapse in the waning moments of a game. Cornell Coach Steve Donahue termed it "the toughest loss of his career at Cornell." He was so troubled by the defeat that he didn't sleep that Saturday night. It would have been a short night for him anyway. He had to leave his house at 3 a.m. to catch a 6 a.m. flight to the West Coast for a recruiting trip. He took the red-eye back Monday night, arriving around noon on Tuesday.

The time away had given him a chance to gain some perspective on the situation. The season wasn't turning out as he or anyone else had hoped. Nonetheless, all was not lost. He felt the need to remind the players that they still could accomplish great things. So before practice that afternoon, he brought the team together.

"You get judged," Donahue told the players. "You judge guys on wins and losses, and when we're at a place like Cornell, it's just a shame that it has to be that way. I know that you guys are high-achieving people who care for each other. I almost wish we had headaches, discipline problems, so that I can get angry at you. But you're great guys. When I was your age I didn't accomplish anywhere near what you have accomplished. You got into this school. You're a Division I athlete. You're achieving great things already. It's hard sometimes to keep it in perspective. These losses are an aspect of life that has nothing to do with how successful you guys are."

Practice that day was fierce. The players were throwing themselves into their work, going all out on defense and playing aggressively on offense. About an hour into the session, during a rebounding drill, there was a scramble for a loose ball underneath the basket. Ryan Rourke and Khaliq Gant dove for it with Brian Kreefer coming in late. The three collided hard. Graham Dow, who was watching from the sideline, was worried about Rourke and Kreefer because it appeared their heads had hit the floor hard.

"I was immediately looking at them because they were woozy and stuff," Dow said. "They're getting up, walking around slowly, and then you look back and see Khaliq still on the floor. Just the way he was lying, you could just sense it was different from a normal injury."

Gant wasn't moving. The sophomore guard from Norcross, Georgia, had no sensation in his arms or legs.

"When I dove for the ball, I heard a loud scream, but I didn't realize initially that was me," Gant said. "I just remember laying there, my body feeling a little bit weird. I was about to get up and I realized I couldn't get up at all."

He was paralyzed. Fortunately, trainer Marc Chamberlain was only steps away and recognized the seriousness of the injury immediately. A call was made to 911. As the players and coaches stood watching in uneasy silence, Chamberlain kept telling Gant to relax and not panic.

"I guess by nature I'm more of a calm person," Gant said. "I was kind of trying to take it in stride. I knew it was pretty serious from the get-go, but I wasn't going to freak out. I knew those kinds of injuries you want to stay relaxed and not add the adrenaline to the injury. . . . I wasn't really thinking about, 'Oh, I can't move.' "

The paramedics arrived. They put a neck brace on Gant and began administering steroids to reduce the swelling. A helicopter landed on the field behind the gym to airlift him to Arnot Ogden Medical Center in Elmira, New York, the closest hospital equipped to handle this type of traumatic injury.

At the hospital with the help of a nurse, Gant spoke to his mom. "Khaliq said to me in his very calm voice, 'Mom, I'm going to be okay,' " Dana Gant said. "Something about the way Khaliq said it, it hit me in a way. It was a knowing that Khaliq felt and knew within the deepest part of his being that he was going to be okay, and I felt that."

Donahue was disconsolate. He couldn't understand how this could happen to one of his players. It had been such a routine play, the kind that happens countless times during practices and games. Yet this one play had taken a vibrant young man and rendered him helpless. One minute Gant, all 6 feet 3, 175 pounds of him, was racing up and down the court with abandon, the next he was lying eerily still in a hospital bed, unable to even wiggle his toes. Donahue, who had spent a lifetime devoted to basketball, now wanted nothing to do with the sport. "I didn't ever want to be in a gym again," Donahue said. "I never wanted to see a young kid play basketball."

Gant's parents, Dana and Dean Gant, arrived from Georgia on Thursday. Had it not been for their fortitude, Donahue might not have been able to cope with this tragedy. They didn't blame anyone or feel sorry for their son's predicament. They wasted no time on pity. Instead, they focused on what it was going to take for their son to recover. "They're unbelievable people," Donahue said. "That's when it hit me. My job is to coach. We have responsibilities as players, coaches."

On Friday, Gant underwent a seven-hour operation. The doctors took a bone graft from his hip and used it to fuse the C4 and C5 vertebrae, then inserted titanium screws and plates for stability. Before leaving for their game at Columbia, several players went to the hospital to wish him good luck. Gant, in turn, wished them luck against the Lions and told them to play hard.

This game mattered more to the Big Red players than any game they had ever played. They wanted to win more than they ever had. Yet, given all they had been through, it would not have been surprising if they lost. They had spent more time worrying about their teammate than preparing for the game. "It's been the hardest week of my life in a lot of ways," Donahue said.

Donahue tends to be an emotional guy. On the sidelines, he bounces up and down, waves his arms, gets in a defensive stance, whistles, and has more facial expressions than a stand-up comic. He wants his players to feed off his energy. But on this day, he was doing all he could to keep his emotions in check. He didn't want to lose it. He didn't want his players to lose it. Easier said than done. Even as the team tried to focus on basketball, reminders of Gant were everywhere. Each player wore a patch with the number 21 -- Gant's number -- on the upper left part of his uniform, close to his heart. Donahue wore a bright red tie with the number 21 embroidered on it.

"Coach told us that the outcome of the game, win or lose, didn't matter to him as long as we went out and gave everything we could on the court for Khaliq," Collins said. "If we played as hard as we could, he told us good things would happen. If we did that, then it didn't matter to him if we won or lost."

Fueled by adrenaline and emotion, Cornell surged to an 8-0 lead. Columbia wisely maintained its poise, weathering the onrush before slowly chipping away at the lead. The Lions went into halftime ahead, 37-34. In the second half, Cornell's guards took over. Graham Dow played his best game of the season, scoring a career-best nineteen points. Adam Gore broke out of his midseason slump, finishing with a career-high 28 points. Cornell went on to win, 81-59.

As the final seconds on the clock wound down, it became impossible for the players and coaches to stifle their feelings any longer. They embraced each other and sobbed on one another's shoulders. They wiped away their tears long enough to shake hands with the Columbia players before heading to the locker room to shed some more. This game had been more trying than they expected. They were exhausted, but relieved to have won.

"In all honesty, I didn't care what the score was going to be today because that's not what this is about," Donahue said. "It's not what Khaliq has to face. It's about trying your best, no matter what. I thought we did that to the nth degree when things could have easily collapsed. . . . I just can't be more proud of a group of guys that I am now."

On the way back to Ithaca from the game, Cornell's bus made a detour. The team went to visit Gant in the hospital. The surgery had gone well. After days of pessimistic prognoses, the doctors were beginning to talk optimistically about Gant's recovery. Everyone was in good spirits, especially Gant. He joked with his teammates, teasing Dow about his turnaround jumper. He clearly shared the team's elation over the win.

No one knew for certain what lay ahead for Gant. Five days after his operation, he was flown by a medical plane to Georgia and taken to Shepherd Center, a spinal-cord-injury hospital in Atlanta, to begin his rehabilitation closer to home. It was still too early to know how much movement, if any, Gant would regain. He would have to endure months of arduous physical therapy. Not wanting him to feel cut off from the team during his time away, a videoconferencing system was set up in Donahue's office. It allowed players and coaches to see and speak with Gant daily. Several players were making plans to visit him during spring break. As he reflected on what the team had been through the past week, Dow realized it was times like this that he was glad he chose to attend Cornell.

"That's the biggest thing with Khaliq and what happened, was how as a team, everybody was there for him," Dow said. "He is like a brother. We wanted to help him as much as we could, help each other try to get through it."

For more information about the book, go to http://www.outsidethelimelight.com.

The time away had given him a chance to gain some perspective on the situation. The season wasn't turning out as he or anyone else had hoped. Nonetheless, all was not lost. He felt the need to remind the players that they still could accomplish great things. So before practice that afternoon, he brought the team together.

"You get judged," Donahue told the players. "You judge guys on wins and losses, and when we're at a place like Cornell, it's just a shame that it has to be that way. I know that you guys are high-achieving people who care for each other. I almost wish we had headaches, discipline problems, so that I can get angry at you. But you're great guys. When I was your age I didn't accomplish anywhere near what you have accomplished. You got into this school. You're a Division I athlete. You're achieving great things already. It's hard sometimes to keep it in perspective. These losses are an aspect of life that has nothing to do with how successful you guys are."

Practice that day was fierce. The players were throwing themselves into their work, going all out on defense and playing aggressively on offense. About an hour into the session, during a rebounding drill, there was a scramble for a loose ball underneath the basket. Ryan Rourke and Khaliq Gant dove for it with Brian Kreefer coming in late. The three collided hard. Graham Dow, who was watching from the sideline, was worried about Rourke and Kreefer because it appeared their heads had hit the floor hard.

"I was immediately looking at them because they were woozy and stuff," Dow said. "They're getting up, walking around slowly, and then you look back and see Khaliq still on the floor. Just the way he was lying, you could just sense it was different from a normal injury."

Gant wasn't moving. The sophomore guard from Norcross, Georgia, had no sensation in his arms or legs.

"When I dove for the ball, I heard a loud scream, but I didn't realize initially that was me," Gant said. "I just remember laying there, my body feeling a little bit weird. I was about to get up and I realized I couldn't get up at all."

He was paralyzed. Fortunately, trainer Marc Chamberlain was only steps away and recognized the seriousness of the injury immediately. A call was made to 911. As the players and coaches stood watching in uneasy silence, Chamberlain kept telling Gant to relax and not panic.

"I guess by nature I'm more of a calm person," Gant said. "I was kind of trying to take it in stride. I knew it was pretty serious from the get-go, but I wasn't going to freak out. I knew those kinds of injuries you want to stay relaxed and not add the adrenaline to the injury. . . . I wasn't really thinking about, 'Oh, I can't move.' "

The paramedics arrived. They put a neck brace on Gant and began administering steroids to reduce the swelling. A helicopter landed on the field behind the gym to airlift him to Arnot Ogden Medical Center in Elmira, New York, the closest hospital equipped to handle this type of traumatic injury.

At the hospital with the help of a nurse, Gant spoke to his mom. "Khaliq said to me in his very calm voice, 'Mom, I'm going to be okay,' " Dana Gant said. "Something about the way Khaliq said it, it hit me in a way. It was a knowing that Khaliq felt and knew within the deepest part of his being that he was going to be okay, and I felt that."

Donahue was disconsolate. He couldn't understand how this could happen to one of his players. It had been such a routine play, the kind that happens countless times during practices and games. Yet this one play had taken a vibrant young man and rendered him helpless. One minute Gant, all 6 feet 3, 175 pounds of him, was racing up and down the court with abandon, the next he was lying eerily still in a hospital bed, unable to even wiggle his toes. Donahue, who had spent a lifetime devoted to basketball, now wanted nothing to do with the sport. "I didn't ever want to be in a gym again," Donahue said. "I never wanted to see a young kid play basketball."

Gant's parents, Dana and Dean Gant, arrived from Georgia on Thursday. Had it not been for their fortitude, Donahue might not have been able to cope with this tragedy. They didn't blame anyone or feel sorry for their son's predicament. They wasted no time on pity. Instead, they focused on what it was going to take for their son to recover. "They're unbelievable people," Donahue said. "That's when it hit me. My job is to coach. We have responsibilities as players, coaches."

On Friday, Gant underwent a seven-hour operation. The doctors took a bone graft from his hip and used it to fuse the C4 and C5 vertebrae, then inserted titanium screws and plates for stability. Before leaving for their game at Columbia, several players went to the hospital to wish him good luck. Gant, in turn, wished them luck against the Lions and told them to play hard.

This game mattered more to the Big Red players than any game they had ever played. They wanted to win more than they ever had. Yet, given all they had been through, it would not have been surprising if they lost. They had spent more time worrying about their teammate than preparing for the game. "It's been the hardest week of my life in a lot of ways," Donahue said.

Donahue tends to be an emotional guy. On the sidelines, he bounces up and down, waves his arms, gets in a defensive stance, whistles, and has more facial expressions than a stand-up comic. He wants his players to feed off his energy. But on this day, he was doing all he could to keep his emotions in check. He didn't want to lose it. He didn't want his players to lose it. Easier said than done. Even as the team tried to focus on basketball, reminders of Gant were everywhere. Each player wore a patch with the number 21 -- Gant's number -- on the upper left part of his uniform, close to his heart. Donahue wore a bright red tie with the number 21 embroidered on it.

"Coach told us that the outcome of the game, win or lose, didn't matter to him as long as we went out and gave everything we could on the court for Khaliq," Collins said. "If we played as hard as we could, he told us good things would happen. If we did that, then it didn't matter to him if we won or lost."

Fueled by adrenaline and emotion, Cornell surged to an 8-0 lead. Columbia wisely maintained its poise, weathering the onrush before slowly chipping away at the lead. The Lions went into halftime ahead, 37-34. In the second half, Cornell's guards took over. Graham Dow played his best game of the season, scoring a career-best nineteen points. Adam Gore broke out of his midseason slump, finishing with a career-high 28 points. Cornell went on to win, 81-59.

As the final seconds on the clock wound down, it became impossible for the players and coaches to stifle their feelings any longer. They embraced each other and sobbed on one another's shoulders. They wiped away their tears long enough to shake hands with the Columbia players before heading to the locker room to shed some more. This game had been more trying than they expected. They were exhausted, but relieved to have won.

"In all honesty, I didn't care what the score was going to be today because that's not what this is about," Donahue said. "It's not what Khaliq has to face. It's about trying your best, no matter what. I thought we did that to the nth degree when things could have easily collapsed. . . . I just can't be more proud of a group of guys that I am now."

On the way back to Ithaca from the game, Cornell's bus made a detour. The team went to visit Gant in the hospital. The surgery had gone well. After days of pessimistic prognoses, the doctors were beginning to talk optimistically about Gant's recovery. Everyone was in good spirits, especially Gant. He joked with his teammates, teasing Dow about his turnaround jumper. He clearly shared the team's elation over the win.

No one knew for certain what lay ahead for Gant. Five days after his operation, he was flown by a medical plane to Georgia and taken to Shepherd Center, a spinal-cord-injury hospital in Atlanta, to begin his rehabilitation closer to home. It was still too early to know how much movement, if any, Gant would regain. He would have to endure months of arduous physical therapy. Not wanting him to feel cut off from the team during his time away, a videoconferencing system was set up in Donahue's office. It allowed players and coaches to see and speak with Gant daily. Several players were making plans to visit him during spring break. As he reflected on what the team had been through the past week, Dow realized it was times like this that he was glad he chose to attend Cornell.

"That's the biggest thing with Khaliq and what happened, was how as a team, everybody was there for him," Dow said. "He is like a brother. We wanted to help him as much as we could, help each other try to get through it."

For more information about the book, go to http://www.outsidethelimelight.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment